Hayv Kahraman: The Foreign in Us

/When I heard that the title of the new exhibit at the Moody Center of the Arts was “The Foreign in Us,” I knew I had to go visit it. "Foreign" is such a powerful word that provokes multiple feelings, preconceptions, misconceptions, points of view, otherness, displacement, and stereotypes.

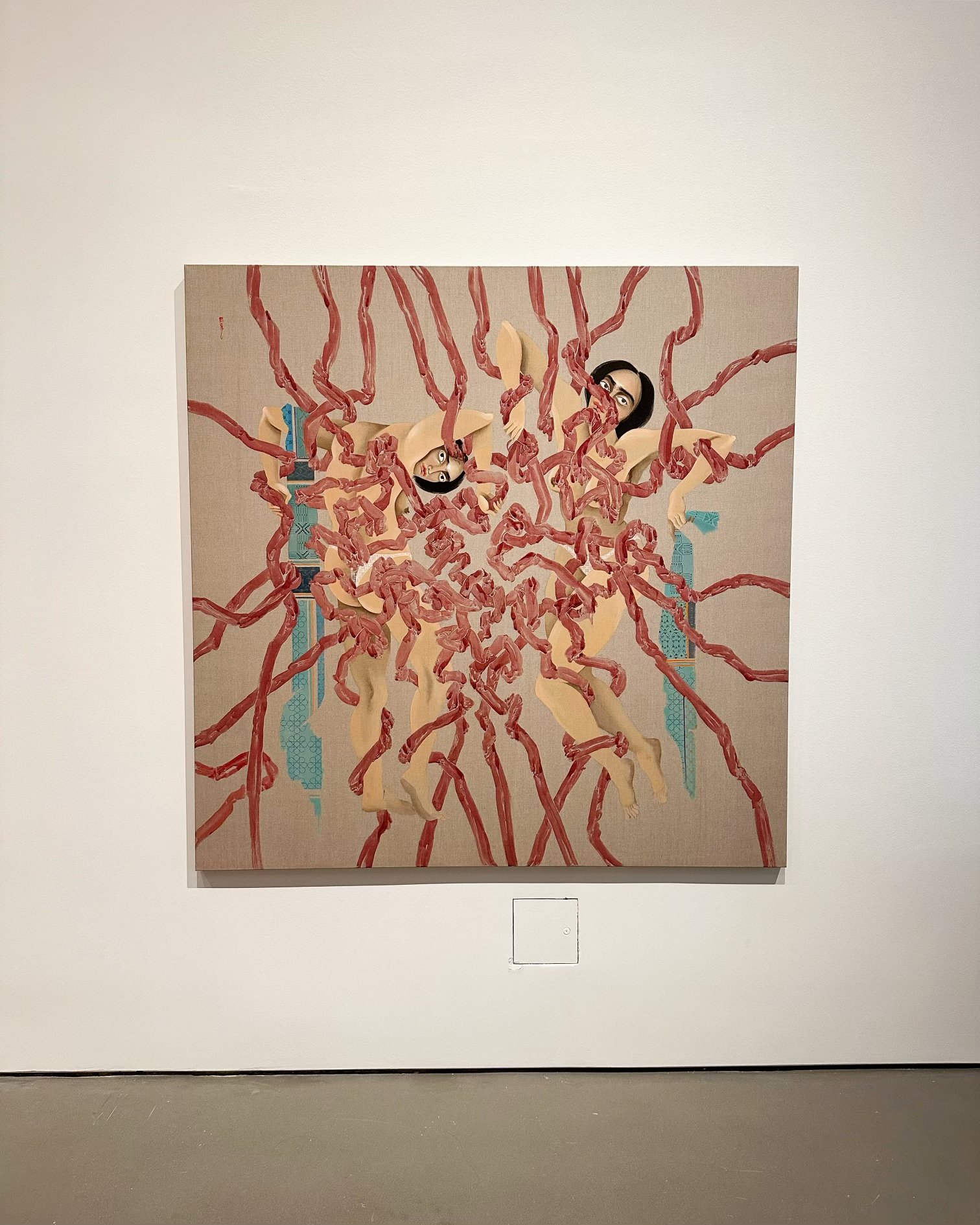

As I walked into the gallery, I was instantly impacted by the images: women's bodies in contortionist postures accompanied by words like antibodies, bacteria, and Torshi.

Definitely intrigued, I started immersing myself in Hayv Kahraman’s work and story. The following is what I learned that transformed the way I understood the word "foreign," and I want to share it with you along with this astonishing artist.

Hayv studied music and ballet in Baghdad when she was little. After many hours of rigorous training, she discovered she could dislocate her shoulder and thigh bone and then pop them back in. She would entertain her friends and family with this original skill that soon became a spectacle.

At the age of ten, she left her country and arrived in the US as a refugee in the 90s. Years later, she started creating paintings with the female body as a central element of her narrative, her memories, and dynamics, a product of her experience as an Iraqi émigré.

“Violently bending bodies are submitting to something. They are becoming what your colonizer wants you to become. Bending so extremely, yet not breaking, without feeling pain. But also knowing you are forced to bend.”

Hayv Kahraman

This mind-blowing statement helped me understand how, influenced by her childhood skill, combined with her migratory experience, brought her to paint these abnormal bodies that bend and twist in these extreme ways. It makes me wonder how many times I have also bent and twisted myself in my own foreign story.

On the other hand, she also talks about how she decided to name some of her paintings with powerful titles such as bacteria and antibodies, just to reiterate through scientific research how our bodies need these foreign forms to survive, expressing a beautiful analogy that advocates for compassion and acceptance.

As part of the exhibition, you will also find a big pink wall painted with Torshi, which, in Middle Eastern cuisine, refers to pickled vegetables. In this case, it is made with beets and red spices—an Iraqi tradition that undoubtedly connects the artist to her lost home.

It’s not a coincidence that this exhibit meets me in a place of deep nostalgia for my country and all the people I left, giving me the strength and hope to continue this life as a bacterium living in another self.

Also, realizing how there’s no need to bend or twist; as foreigners, we just need to integrate our true selves into this foreign body to help it not only grow but survive.